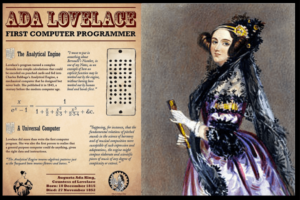

Early Life and Unique Education

Ada Lovelace, born Augusta Ada Byron on December 10, 1815, in London, was the only legitimate child of the famous poet Lord Byron. Her parents separated when she was just a month old, and she never saw her father again. Lady Anne Isabella Milbanke, Ada’s mother, took full control of her education. Unlike the typical Victorian focus on literature and etiquette for girls, Ada’s upbringing revolved around mathematics and logic. Her mother feared that Ada might inherit her father’s unpredictable and volatile personality. As a result, she believed that rigorous mental training could prevent emotional instability.

From a young age, Ada displayed a unique fascination with machines and numbers. By age 12, she had already conceptualized a flying machine, based on bird anatomy. Her sharp intellect didn’t go unnoticed. Ada studied under some of the most brilliant minds of her time, including Mary Somerville, a renowned mathematician, and scientist. This education in logic and mathematics became the foundation of her groundbreaking contributions later in life. Somerville also introduced Ada to Charles Babbage, a meeting that would change both their lives and shape the future of computing.

Meeting Charles Babbage and the Analytical Engine

In 1833, Ada was introduced to Charles Babbage, a mathematician and inventor famous for designing the Difference Engine, an early mechanical calculator. Ada’s keen intellect immediately impressed Babbage, and they formed a close intellectual partnership. Babbage shared his designs for a new, more advanced machine—the Analytical Engine—which would go beyond simple calculations to solve more complex equations. This machine had the potential to be the world’s first general-purpose computer, long before anyone else could envision such a concept.

While Babbage designed the hardware, Ada’s vision was far more revolutionary. She saw the possibility that machines like the Analytical Engine could do more than compute numbers. Ada recognized that these machines could be programmed to execute a sequence of instructions. Moreover, she imagined that computers might one day handle not only numbers but also symbols, and thus be capable of composing music, creating art, and more. Her foresight went beyond the physical machine, peering into a future where computation could shape the world.

Ada’s Historic Algorithm: The Birth of Computer Programming

In 1842, Ada was tasked with translating an article by Italian mathematician Luigi Menabrea about Babbage’s Analytical Engine from French to English. However, Ada didn’t stop at translation. She added her own extensive notes to the article, explaining the engine’s potential in greater detail. Her notes ended up being more than twice the length of the original work. In these notes, she included a step-by-step method for calculating Bernoulli numbers using the Analytical Engine—a process now recognized as the first computer algorithm ever written.

Ada’s work laid the foundation for modern computer science. Her vision was far ahead of her time, as she understood that machines could do much more than follow basic arithmetic operations. She saw them as capable of being instructed to follow complex sequences of operations, what we now call programming. Her notes included concepts of loops, conditionals, and subroutines—ideas that remain central to programming today. Without Ada’s vision and theoretical work, the progression to modern computing might have taken far longer.

Personal Life and Struggles

In 1835, Ada married William King, who later became the Earl of Lovelace, and Ada became the Countess of Lovelace. The couple had three children: Byron, Annabella, and Ralph. Despite her aristocratic life, Ada’s passion for mathematics remained a constant. She continued her studies and correspondence with Babbage even after becoming a mother. However, Ada faced many personal struggles, including chronic health problems. She frequently fell ill, likely exacerbated by her growing reliance on pain medications. Ada also grappled with issues related to her personal finances, as she engaged in gambling schemes that placed her in debt.

While Ada had an active intellectual life, her personal life was marred by these challenges. Sadly, at the age of 36, Ada Lovelace died from uterine cancer in 1852. Her final days were spent reflecting on her life and work, expressing remorse over some of her decisions, especially related to her gambling. However, her intellectual contributions remained her lasting legacy. Although her life was short, her work would go on to inspire countless others in the fields of mathematics and computing.

Legacy and Recognition

Ada Lovelace’s contributions were largely forgotten after her death, but researchers rediscovered her work in the mid-20th century. Today, people recognize her as the first computer programmer in history. The U.S. Department of Defense named a computer programming language “Ada” in her honor in 1980, further cementing her place in the history of computing. Ada’s work has had a lasting influence, not only because she was the first to recognize the potential for computers to move beyond simple arithmetic, but also because she demonstrated that technology could be a creative, transformative force in society.

People celebrate Ada Lovelace Day annually in October to honor her achievements and inspire women to pursue careers in science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM). Ada’s legacy as a visionary thinker and the first computer programmer has paved the way for generations of technologists, both men and women. Her life serves as a reminder that ideas—no matter how ahead of their time—can eventually change the world. Ada Lovelace saw the potential of machines in a way that no one else of her era did, and her vision set the stage for the digital age we live in today.

Detailed Information

| Full Name | Augusta Ada Byron, Countess of Lovelace |

|---|---|

| Born | December 10, 1815, London, England |

| Died | November 27, 1852, London, England |

| Nationality | British |

| Education | Private Tutors, Mentorship by Mary Somerville |

| Occupation | Mathematician, Writer, Computer Programmer |

| Known For | First Algorithm for a Computing Machine, Visionary of Modern Computing |

| Parents |

|

| Spouse | William King-Noel, 1st Earl of Lovelace |

| Children |

|

| Major Works |

|

| Honors |

|

| Legacy | Inspiration for Women in STEM, First Computer Programmer |